By now, most somewhat sober Semper Floreat readers will be somewhat cognizant of Facebook’s brash response to the federal government’s then proposed Media Bargaining Code. The week-long ban saw key public information – such as the Bureau of Meteorology’s severe weather warnings, QLD Health’s pandemic-related updates, rural and indigenous local news, and advice surrounding domestic violence and homelessness shelters – painted with the same broad brush as all other forms of news media. Per Facebook, this was due to the then Bill’s broad definition of news; in reality, the move was a tantrum about being dragged to the table.

context

In April of 2020, the Federal Government tasked the ACCC with devising a mandatory code of conduct to govern the relationship between Australian news media entities and online platforms/services. Beyond permitting news entities to bargain – collectively or individually – for financial recognition of original media, the Code outlines minimum standards for the usage – by corporations like Facebook and Google – of Australian news media. The Code’s framework emerged from amongst a range of early stakeholder suggestions, including collective boycotting and funding pool arrangements, and ultimately proffers negotiations followed by mediation and arbitration. So, though the Code does indeed look set to redress the presupposed “power imbalance” between Australian news media and its internet platforms, the Code neglects to address imbalances rife amongst Australian news media corporations themselves.

Federal President (Media) – of the Media, Entertainment and Arts Alliance (MEAA) – Marcus Strom emphasised the negotiations value of the arbitration threat posed, as reportedly manifest in the resultant mid-February content-deals between Google and Nine Entertainment (et cetera), and supports generally the Code’s impetus for bringing other platforms to the table. Mr Strom pressured the government on media corporations’ transparency broadly and over the specific stipulations: that future governments not use relationships established under the code as a justification for cuts to the ABC and SBS (the kneejerk solution per the finalised Act – removing publicly-funded broadcasters from the Code entirely – is equally problematic); and, that corporations “commit to allocating the funds [(those acquired pursuant to the Code)] to journalism, and not [to] other parts of their organisations”.

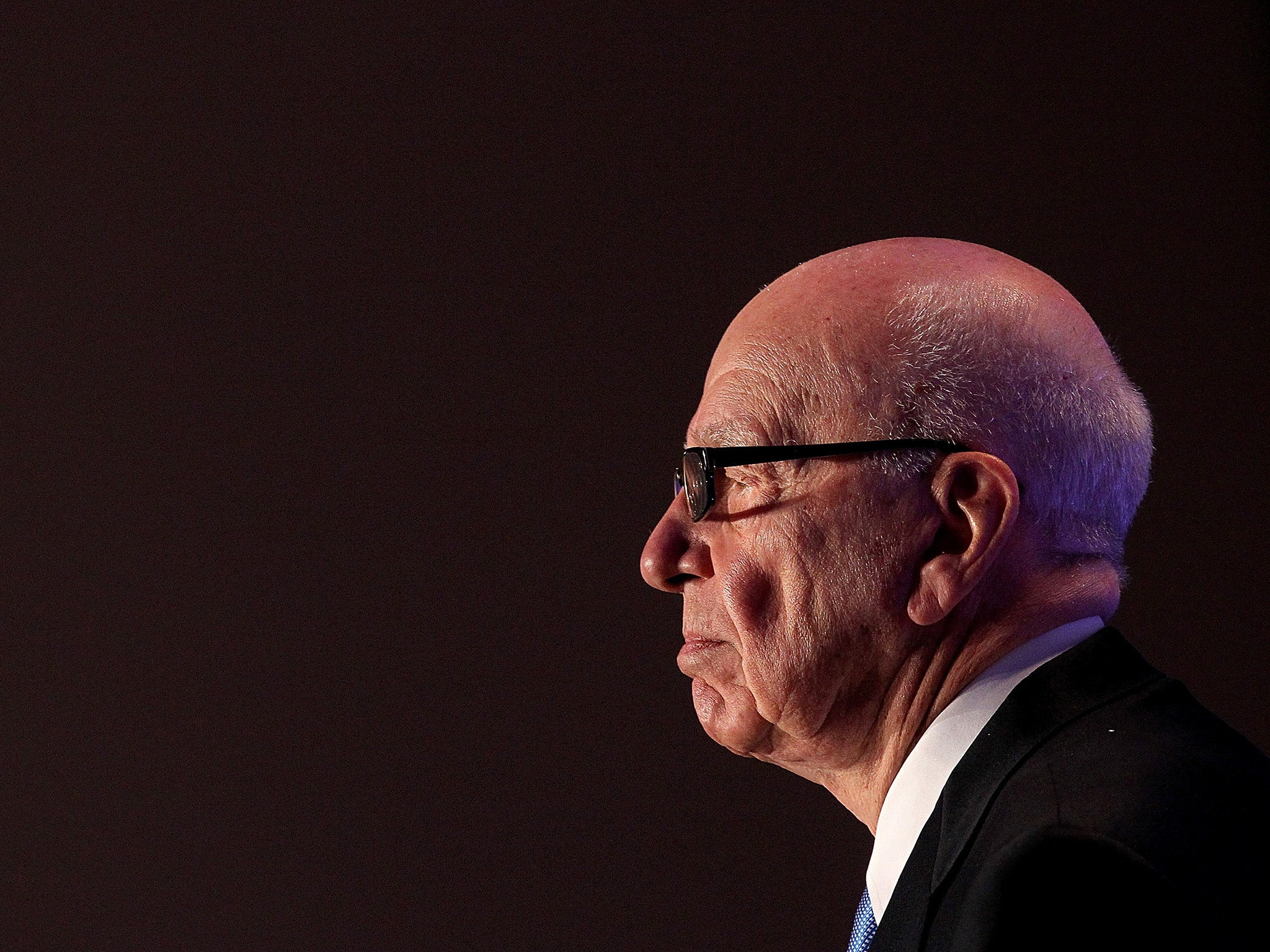

This latter stipulation was central to the MEAA’s submission, on the bill, and is indicative of how the Code might otherwise strengthen Murdoch’s stranglehold on the broader media landscape. Indeed, the majority of political commentary has been that Facebook is largely amoral, and that contemporary governments misunderstand the depth of that amorality, which becomes a wholly circular and self-defeating observation insofar as Murdoch’s News Corp empire can be credited with influencing pseudo-democratic elections everywhere and could further monopolise – on its greater pre-existing market share alone – through simply reinvesting funds acquired under the Code. Of course, for Murdoch, this is a positive feedback loop (of capital) atop which he sits.

student journalism

For Semper and other student-group publications, concerns are rooted in perceived trends towards student union obsoletion in the face of rampant university corporatism. The National Union of Students noted that, in unfolding at the beginning of semester, Facebook’s ban left many without timely access to information surrounding student-led services and events. Curiously, though, much university-brand media remained largely unaffected by the ban. Whether this was because of the platform’s algorithm, user configurations which tagged these institutions as distinct from student-run news media, or a flawed characterisation by Facebook of university news media as academia and therefore exempt, is the object of pure speculation.

Communications Minister Paul Fletcher expects direct negotiations between platforms and smaller media groups to occur “albeit through a more efficient mode of engagement through a default offer” which is, in my view, the economic/social equivalent of unnecessarily prolonging bleeding while overstimulating the heart. Moreover, default offers will likely not be very favourable insofar as the offers’ incentive for existence will be as a means of appeasing the government (read: satiating the Morrison Government’s publicity quotas), rather than out of a desire to see good journalism flourish. Though student media organisations could – alternatively – negotiate together, they will ultimately lack the resources necessary for putting cases through the Code’s arbitration stage. Universities are, to the contrary, well equipped themselves or together.

So, the task falls to student news media to stem its own bleeding. Various methods come to mind, though the most important will be – from my perspective – reinvigorating the communalistic appeal of student led media and better fostering the political rebirth of student bodies.

the truth

Paradigmatic of the revolving-door scapegoatism underpinning discourses surrounding “Big Tech” (Trump’s laboured hypocoristic for online platforms), News Corp and competing mafias, and the federal government or specifically the two-party system, is Facebook claiming it is battling false news whilst benefiting from its tumorous growth. Moreover, that Facebook can manipulate and re-direct news is perhaps more powerful than specific media creation itself (NB: advising news media groups in advance of changes to algorithms forms part of the Code); indeed, some argue tech giants’ power over political discourse would otherwise outstrip outfits like News Corp, making the new Bargaining Code a deus ex machina for Murdoch media – particularly if the European Union and Canada also enact similar codes, sooner rather than later.

Stay tuned, nonetheless, because Facebook has not ruled out reinstating its ban on Australian news media, which, particularly if it is formally designated under the Code, is probably not an empty threat. This is particularly likely if Facebook is formally designated under the Code. For now, however, formal designation is operating as the government’s ‘stick’, whereas making pre-emptive offers is the ‘carrot’ since those have been and will be impliedly lesser value than would otherwise ensue designation. Ultimately, this is as telling as it is itself problematic: the government does not care whether the nation’s news media in its entirety – which is, per its peoples, diverse – gets a good deal.

Views: 54